Opinion

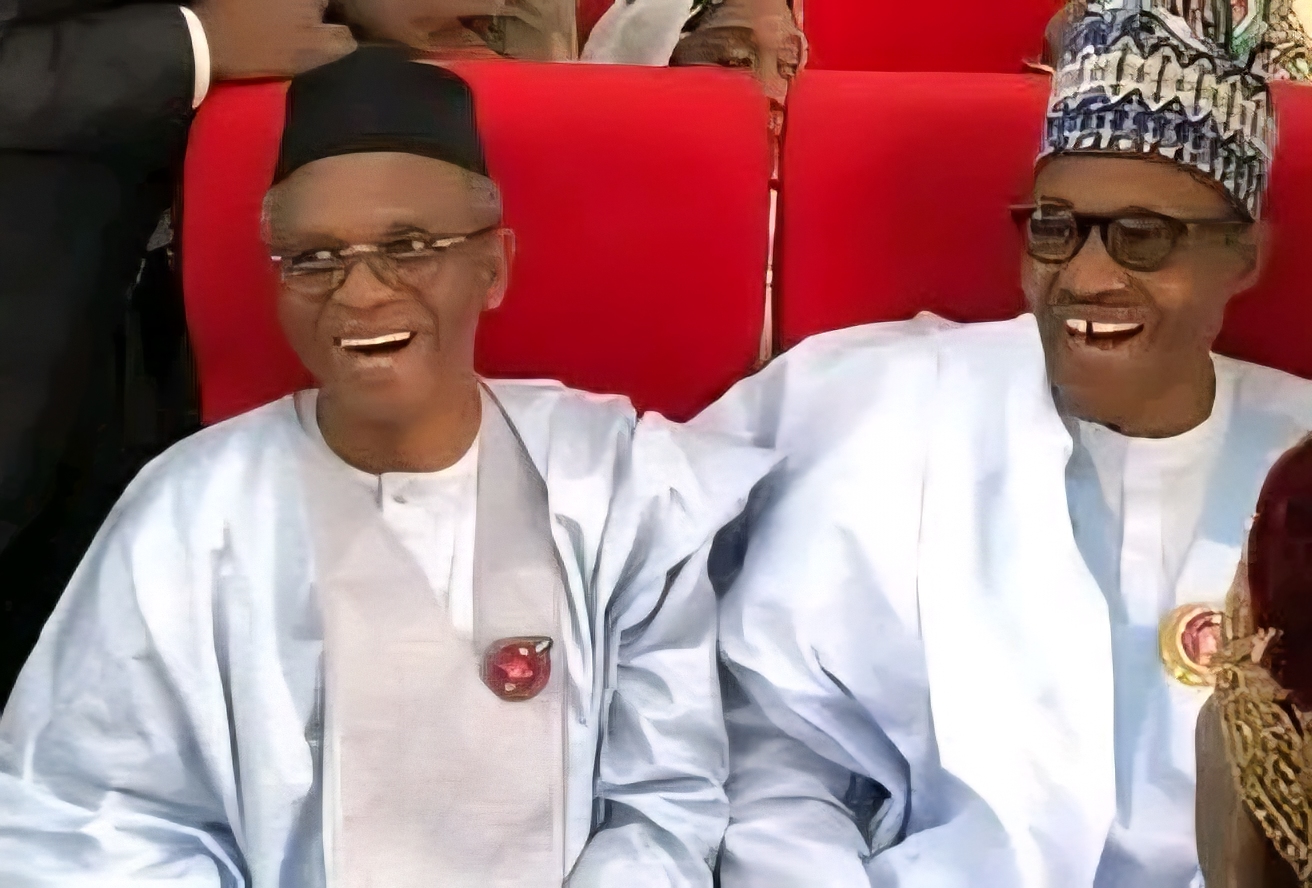

“Let President Muhammadu Buhari Rest in Peace” – By Nasir El-Rufai

The recent launch of a book on the life and legacy of our late leader, President Muhammadu Buhari, has stirred deep emotions and renewed divisions among those who once formed his inner circle. Having followed the headlines and images from the event, I felt compelled to make a simple but urgent appeal: let us allow President Buhari to rest in peace.

A careful look at those who dominated the book launch revealed the same factional lines that existed during Buhari’s lifetime. One camp was prominently represented, while others—equally close to the late president—were excluded. This selective engagement compounded by the choice of location of the event were red flags, and raises concerns about whether Buhari’s legacy is now being shaped to serve narrow interests rather than historical truth.

More troubling was the presence of long-time critics of Buhari, some of whom now hold high office, delivering glowing, but clearly faked tributes. These are individuals who once blamed his administration for nearly every challenge facing Nigeria, but who now appear eager to revise history—perhaps to deflect responsibility for present failures.

It was also unsettling to see individuals celebrating Buhari in death who had neither his trust nor his respect in life. President Buhari was a principled man who did not easily forget personal or political disrespect, and he made his preferences clear to those around him.

I have not yet read the book, Soldier to Statesman: The Legacy of Muhammadu Buhari, and it is possible that some media reports lack context. However, many of the so-called revelations attributed to the late president appear one-sided and unfair, especially as he is no longer alive to respond. Explaining the thoughts and motivations of a complex leader through selective anecdotes risks distorting, rather than preserving, his legacy.

President Buhari was far from perfect. Many of us who supported him expected much more from his civilian presidency. However, as someone who worked closely with him in opposition political, and governance roles for over a decade, I believe much of his administration’s shortcomings stemmed from the actions and failures of a powerful inner circle—relatives, advisers, and officials who did not always share his commitment to integrity and public service.

Buhari himself remained, to the end, a man of deep faith, personal discipline, and unquestioned patriotism. Those now invoking his name for self-justification should reflect on whether they can claim the same standards.

My appeal here is simple: to all Nigerians: admirers and critics alike—let President Muhammadu Buhari rest in peace. Let history judge him fairly, without opportunism or revisionism. The truest way to honour him is not through selective storytelling, or attempting to exhibit new-found love, but by upholding the values he embodied: simplicity, integrity, humility, and service to Nigeria with all he had.

May Allah grant him eternal rest.

Nasir Ahmad El-Rufai

Cairo, Egypt

17th December, 2025

Opinion

APC E-registration Plot To Manipulate 2027 Polls – Ogun LP

The Ogun State chapter of the Labour Party has accused the All Progressives Congress of using its ongoing electronic membership registration to allegedly manipulate figures ahead of the 2027 general elections.

In a statement issued on Wednesday, the state chairman of the Labour Party, Chief Oluwabukola Soyoye, claimed that the APC’s e-registration exercise was designed to digitally inflate its membership strength and project a false image of popularity in the state.

Soyoye alleged that the ruling party had resorted to electronic registration because it could no longer mobilise people openly, insisting that the administration of Governor Dapo Abiodun had suffered widespread rejection due to what he described as underperformance.

According to him, the APC’s e-registration, presented as a routine membership drive, was in reality “a political referendum that exposes the deep rejection of Governor Dapo Abiodun and his black-market style of governance by the people of Ogun State.

“The people of Ogun are now wiser. They have deliberately refused to participate in any open, physical APC registration because they know the ruling party has failed them,” Soyoye said.

“That is why the APC has resorted to this so-called electronic registration — a system that allows figures to be fabricated behind closed doors without the presence of real members.”

The LP further alleged that the electronic platform could be used to manipulate membership data, inflate figures and create a misleading narrative of political dominance ahead of 2027

“What we are witnessing is not a genuine political exercise but a fraudulent digital operation designed to manufacture legitimacy for a government that has lost the confidence of the people,” Soyoye added.

Opinion

Let These Campaigns Of Calumny Against AMBO Stop Forthwith

By Kola Odepeju

“Calumny Is Only The Noise Of Madmen” –Diogenes

As Osun state gubernatorial election draws nearer, we’re now at the dawn of the campaigns for the coming election and so as characteristic of Nigeria’s democracy, wrong accusations, blackmails, character assassinations and all manner of negative campaigns aimed at demarketing the most popular candidate with the highest chances of coasting home to victory in a major election of this nature, must surface. And so in our own dear Osun state here this ugly trend has started surfacing. The mudslinging that has started from Governor Ademola Adeleke’s Accord Party’s camp against the APC gubernatorial candidate, Asiwaju Munirudeen Bola Oyebamiji AMBO is ‘normal’ and expected because with the massive support for AMBO across the nook and cranny of the state, it’s crystal clear that he’s the candidate to beat.

As mentioned above, a candidate to beat in any major election is bound to face vilifications by his opponents who see him as a threat and a stumbling block against the success of their own ambitions. Therefore given the nature of our politics in this part of the world, the negative campaigns that have started against AMBO are no surprise. We witnessed the same thing against the incumbent president, Asiwaju Bola Tinubu during the 2023 electioneering campaigns for the office of the country’s president. But against all odds, Asiwaju Tinubu emerged victorious. So as Asiwaju Tinubu emerged victorious in 2023, l have that strong conviction that our own Asiwaju Bola Oyebamiji will also become victorious in the coming August gubernatorial election in the state irrespective of whatever negative campaigns that may come up against him. This is because the AMBO governorship project is divinely ordained.

Amongst other attacks that are still likely to come up against him as we face the election and as the election faces us, we have heard from those who are afraid of losing power that AMBO is the architect of half salaries in Osun (as if he was the governor in that era). We have also heard from them that he’s not youth-friendly. The spokesperson to governor Adeleke, Malam Olawale Rasheed also amplified these two negative points in his latest article aimed at demarketing AMBO. Like I mentioned, the negative campaigns have just started. We are still going to hear more. I wonder why people cannot engage in issues-based campaigns instead of vilifying candidates.

Ambo has told Osun youths the program he has for them. He has promised to take care of them. And as a God-fearing and honest leader who keeps to his words, l believe he will not renege on his promise for the youths and also his promises for Osun people generally. So let those who revel in vilifying a credible candidate like AMBO tell Osun youths the programs they have for them rather than calumniating a visionary and capable leader who has what it takes to deliver the goods. Of course AMBO – being a focused leader – needs not to bother himself about the negative campaigns being circulated against him by his political detractors because William Shakespeare had for long told us that “*Be thou as chaste as ice, and as pure as snow, thou shall not escape calumny*”. And George Washington also mentioned it that “*Silence is the best answer to false accusations*”.

Finally, the Yorubas in their words do say that “maligning the honey doesn’t reduce its sweetness”. No matter the level of negative campaigns against the APC gubernatorial candidate towards the election, it won’t reduce the love the Osun people have for him while it won’t deter them from casting their votes for him in the upcoming gubernatorial election in the state. He will surely come out victorious by the special Grace of God Almighty 🙏. For, Vox populi vox dei. AMBO should continue on the path of issues-based campaigns and close his eyes against malignant talks by those who are already on their way out of power.

● Odepeju, newspaper columnist and political activist, writes from Iragbiji, Osun state.

Opinion

Ogun 2027: Kings Have Spoken, Yayi Belongs, Let the Campaign Begin

-

Politics2 days ago

Politics2 days ago2027: Peter Obi Rejects Vice President Role, Declares Next Political Move

-

Politics2 days ago

Politics2 days agoAPC Break Silence On Shettima’s Appointment As Vice President In 2027

-

Politics15 hours ago

Politics15 hours agoBREAKING: Tinubu Reportedly Issues Strong Orders To wike And Fubara

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoFCT: Court Bars NLC, TUC, Others From Embarking On Planned Protest

-

Sports2 days ago

Sports2 days agoTransfer: Cristiano Ronaldo blocks moves for Benzema, Kante

-

Sports2 days ago

Sports2 days agoTransfer: Aribo seals loan move to Leicester City

-

News15 hours ago

News15 hours agoREVEALED: Details Of Alleged Terrorism Financing Charge Against Ex AGF Malami

-

Entertainment2 days ago

Entertainment2 days agoGrammy 2026: I am disappointed in Chioma – Delta Gov’s aide